It’s Not Easy Being Green: Is Europe’s Green Wave receding?

The Greens had their strongest-ever showing in the 2019 European elections, but many media sources — including Politico’s Poll of Polls and Europe Elects — now predict that the Greens will be the “biggest losers” of the 2024 elections. In the past 5 years, the Greens have experienced wins and losses, but recent national elections have seen Green parties’ support plummet in countries where they did very well in previous elections.

The Greens had their strongest-ever showing in the 2019 European elections, but many media sources — including Politico’s Poll of Polls and Europe Elects — now predict that the Greens will be the “biggest losers” of the 2024 elections. In the past 5 years, the Greens have experienced wins and losses, but recent national elections have seen Green parties’ support plummet in countries where they did very well in previous elections.

The loss of support for the Greens does not necessarily mean that voters no longer care about climate change; rather, it could be due to several factors. First, other crises have taken centre stage - including COVID-19, wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, the energy crisis, inflation, and the rising cost of living. The cost of green policies is gaining more attention and criticism as citizens worry about how the green transition will be paid for. Second, in countries where Green parties are in power, they are in coalitions in which they are required to compromise and make concessions. This has made some of their supporters feel that Green parties have not done enough to fulfil their campaign promises. Third, the Greens suffer from a reputation in which they are seen as being out of touch with the “average” person. Finally, other political parties have begun to include the climate in their priorities and campaign on green issues, meaning that support for the Greens has become fragmented.

There is still a lot of time remaining before the 2024 European elections, and it is too early to declare the death of the Greens. Even if they do lose as many seats as predicted, this won’t necessarily lead to less ambitious EU climate legislation.

As we speed towards the next mandate - one that will be essential in setting up the EU to meet its 2030 and 2050 climate targets - policy professionals need to know why the Greens are predicted to lose so many seats and what’s at stake for the future.

The Greens’ Position: 2019 vs Today

Will the Greens sediment their political weight in the EP in the 2024 European elections, or are they facing a “Green low tide” ahead of the 10th term?

The Greens are currently polling between 45 and 50 seats depending on estimates, with the most recent estimate in the Poll of Polls granting them 45. The Greens currently represent the 4th largest political force in the European Parliament (EP) with 72 seats. According to this projection, they would fall to 6th place in the next term, greatly diminishing their political weight. Before declaring the death of the Greens in the EP, however, there are a few points of caution that should be considered.

In late 2018, the Greens were in a similar position in the polls as they are today. Then, the polls only credited the Greens with around 45 seats, whereas they managed to secure 22 more after a campaign marked by important mobilisation on climate-related issues. The upcoming campaign could still benefit the Green group in the next term. The affiliation of new parties that have flourished since the last European election to the Greens/EFA group could also benefit the group and mitigate the current estimated loss.

The Greens’ success in 2019 was, in part, attributed to the magnitude of civil society mobilisation and youth movements such as ‘Fridays for Future’. Greta Thunberg’s School Strike for Climate began in late 2018 and gained a lot of traction in global media. The return of Climate March in Brussels earlier this month could be an attempt to repeat this scenario that saw the rise of the 2019 ‘Green Wave’.

However, governments have recently started to crack down on the very same youth climate protesters that were credited with the green wave. Greta Thunberg herself was charged with disobeying Swedish police during an oil protest. Similar arrests of climate protesters across Europe led United Nations experts, the Council of Europe and other rights groups to “warn that European countries are increasingly employing disproportionate methods to stymie climate activism”. It seems unlikely, then, that climate activists will come to the aid of the Greens again in the next European elections.

Another difference between 2019 and today is that the Greens did exceptionally well in several national elections that took place in the time leading up to and immediately after the 2019 European elections. In contrast, the Greens have done exceptionally poorly in these same countries in recent elections. The numbers can shed light on the situation.

Wins & Setbacks Across Europe: National Cases

While the national political dynamics never translate perfectly to European elections, assessing the Greens' success in the past five years could help us assess their success in the upcoming polls.

Relative success in some Member States

There are currently 5* EU countries that have green parties in government:

- Die Grünen in Austria

- Groen/Ecolo in Belgium

- Bündis 90/Die Grünen in Germany

- the Green Party in Ireland

- and Déi Gréng in Luxembourg

- *Sumar in Spain is currently an unconfirmed affiliation and could join the Greens during their upcoming Congress in Lyon

4 of these 5 countries are also on the list of the seven countries where climate change is considered the most serious problem facing the world by respondents according to a Eurobarometer survey: Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, and Sweden.

Several of these countries where citizens prioritise climate change held elections recently. Bavaria and Hesse in Germany as well as Luxembourg held elections on 8 October. Finland also held elections earlier this year, in April. Despite the Greens being successful in these countries in the past, the Greens had particularly bad showings in these elections.

Recent Setbacks

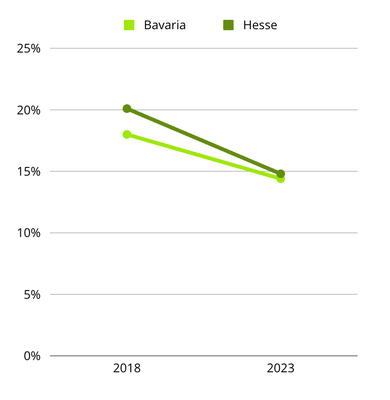

Germany - Bavaria & Hesse In Bavaria, the Grune party had 18% of the vote in 2018, and only 14.4% in 2023. The loss in Hesse was even more significant, moving from 20.1% of the vote in 2018 to 14.8% in 2023.

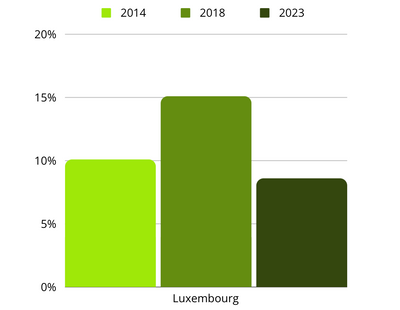

Luxembourg In Luxembourg, the Greens (Déi Gréng) had 15.1% of the vote in 2018 and 8.6% in 2023. Luxembourg also held national elections shortly before the 2019 European elections, on 14 October 2018, when the Greens won 15.1%, up from 10.1% in 2014. This could have been an early sign of the “green wave”, while the loss of the Greens in the most recent elections could also be interpreted as a predictor of Green losses to come.

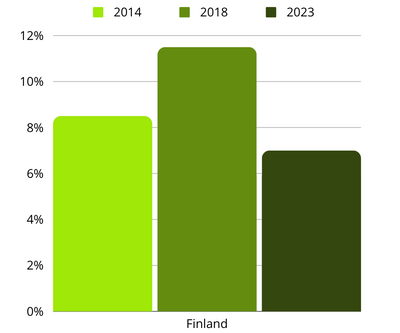

Finland In Finland, the Green League (Vihreä liitto) held 11.5% of the vote in 2019, and only 7% in 2023.

Like in Luxembourg, signs of the “green wave” were present in Finland around the time of the 2019 European elections. On 14 April 2019, the Greens in Finland won 11.5%, up from 8.5% in 2015.

The Netherlands Most recently, the Netherlands held elections on 22 November which saw Geert Wilders’ far-right nationalist Freedom Party (PVV) win 37 seats. Former Executive Vice President of the European Commission for the European Green Deal and European Commissioner for Climate Action Frans Timmermans’ socialist and green party coalition (PvdA/GL) was the runner-up with only 25 seats.

Getting the second-highest number of votes should not necessarily be seen as a setback, although it is impossible to tell how much of this result was due to support (or lack thereof) for the Greens versus the Socialists. However, Wilders’ victory represents the first time a party openly calling for an end to the green transition has won a national election in the European Union.

Does all of this mean that the green wave is over and citizens no longer care about climate change?

Not necessarily. Citizens’ concern about climate change does not always translate into more votes for Green parties. Even though the Greens are not doing well in the polls, Europe-wide data shows that climate change is still a priority for European citizens. A Eurobarometer survey from July 2023 showed that more than three-quarters (77%) of EU citizens think climate change is a very serious problem at this moment. The same survey showed that 56% of Europeans think their national government and the EU are responsible for tackling climate change, and 67% think their national government is not doing enough to tackle climate change.

So why are Green parties losing so much support? Can we expect the Greens’ fate in the European elections to follow the trend of some of the recent national elections?

Examining why the Greens have lost support nationally can help us to understand why polls expect the Greens to be the biggest losers in the European elections.

4 reasons the Greens may have lost support:

1. The Greens are doing too much in times of other crises

Perhaps the most visible reason for the decline in support for Green parties is that in the context of COVID, the war in Ukraine, the cost of living crisis, the energy crisis, inflation, and war in the Middle East, the cost of green policies for the average citizen is receiving more and more attention.

This was clear in Germany when the government decided to delay the shutdown of the nuclear plants. While some criticised the delay, more still criticised the decision to shut the plants down at all when prices were so high and supply so low.

The nail in the coffin was the German Greens’ support of a new law requiring that newly installed home heating systems run on at least 65% renewable energy starting next year. The proposal of this law is widely cited as bringing the German government to its knees. In the context of the many economic difficulties and uncertainties being faced by so many citizens, “the Greens were easily caricatured as a party oblivious to people’s struggles.”

This trend is also prominent within the EP. Greens MEP Jutta Paulus has previously stated that “many parties are currently afraid to talk about the environment at all, because the argument immediately comes up that we have completely different crises now, as in Ukraine and the Middle East, and we have to stop with the [so-called] ‘flowery stuff.’”

2. A Bad Reputation

This perception that green policies are putting financial pressure on citizens during times of crisis has led to Green parties having somewhat of a bad reputation. Markus Ziener, a visiting fellow at the German Marshall Fund, said of the Greens: “they squandered a lot of their success because they seemed detached from ordinary people. Instead of setting incentives, they were seen as telling people what’s right and what’s wrong, as wanting to lecture people.”

This phenomenon is not limited to Germany. Chair of the Finnish Green Council group Sofia Virta said after the Greens’ “heavy” defeat in the elections that took place in April: “the image of the Greens as an arrogant and hermetic party must be altered, and there is no correct way to support and vote for them”.

This idea that the Greens are “arrogant” and “morally superior” was also reflected in polls on Dutch sentiment towards Timmermans during his campaign for the Prime Minister position: only one-third of Dutch voters found Timmermans acceptable as Prime Minister. While 94% believed he knows a lot about world politics and 78% believed he is trustworthy, Timmermans’ weakness was that only 33% felt that they could identify with him as a person. One voter said, “his experience in particular is a plus for me, but as a person, he is a lot of who I am not: old, Limburgish, a bit too vain".

Why do the Greens seem to have this reputation of being vain, arrogant, and morally superior? Habeck suggested it is because the Greens had to claim to have access to a higher form of truth as a grassroots movement. It could also be because people generally don’t enjoy being told that they are destroying the planet by going about their daily lives - driving their cars and heating their homes - and that they feel judged by those who tell them they are doing something wrong. This is particularly true when other crises are putting pressure on peoples’ wallets, and green solutions are perceived as being (and in many cases actually are) very expensive for individuals. In the current market, electric cars tend to cost more than diesel cars, and renovating a poorly insulated home comes with a huge price tag.

The campaign for the 2024 European elections will show how well the Greens can overcome their reputation and relate to “ordinary people”. In an interview with EURACTIV, Terry Reintke, co-president of the Greens/EFA group, emphasised that social justice will be a priority during the campaign. She said: “we see that there is a growing divide between rich and poor in our societies, and now even exacerbated by the crisis. So we want to talk about good working conditions, good wages, why the EU should have a stronger role there”.

Focusing on these issues during the campaign will also be essential to overcome the argument that the Greens are “doing too much” at a time when European citizens are facing many crises and have become wary of the costs of the green transition.

3. The Greens are not doing enough about the climate crisis

The backlash from these various crises and the lack of support to push green legislation forward has meant that some climate actions have been rejected, watered down or even reversed. As a result, Green parties are being criticised by their supporters for not doing enough. This could have caused Green voters to become “demoralised”.

Graffiti found in Germany’s capital said “Green is getting too brown”. The Greens were being criticised by hard-line environmentalists for being “soft”. The context was that, in the context of a coalition, Greens agreed to crank up coal power to replace lost imports of Russian gas and to delay by six months the long-planned shutdown of Germany’s last three nuclear plants.

Green parties are caught between a climate crisis and a hard place, which is characterised by many crises that are burdening citizens. Trying to find the balance between moving forward with ambitious climate policy while also avoiding any extra costs to citizens has proven to be a near-impossible task. The demoralisation of Green voters is in sharp contrast to 2019 when citizens, and especially young people, were inspired to protest, march and speak out in favour of the Greens.

4. Fragmentation

A final explanation for Green parties experiencing declining support is that they no longer have the monopoly on campaigning on green issues. Other political parties have started including climate in their priorities.

From a Dutch perspective, Green MEP Bas Eickhout said: "behind corona, climate is basically the first [concern], together with the economy. So, it is a super big issue in the elections ... but in the Dutch electoral system, it’s been fragmented across parties, unfortunately, from our perspective".

This means that while a majority of voters might care about climate issues, they will not necessarily vote for Green parties. Instead, they could choose to vote for another party that campaigns not only on climate issues but also on other issues that are important to them.

On a European level, earlier this year NGO BLOOM analysed the environmental performance of all MEPs according to their votes on 11 texts relating to the climate, the ocean, and biodiversity, adopted during the current legislature. Unsurprisingly, the Greens scored the highest with 19.2/20. However, the Left and S&D groups were not far behind, with 17,5 and 16,4 respectively. BLOOM highlights that S&D campaigned heavily on climate issues in 2019 and centred their programme around the Sustainable Development Goals, and their score shows they kept their campaign promises.

While fragmentation is a compelling argument for why Green parties may be losing out in the polls, it is not The Left and S&Ds who are capturing those lost votes by campaigning on climate issues. Polls suggest that the far-right political parties are reaching record highs in terms of support. These parties tend to be less ambitious when it comes to climate action, as evidenced in the BLOOM study in which ID and ECR scored quite low, with 4,5 and 3,5 respectively.

While the Greens and other progressive movements used to incarnate the only vote in favour of sustainability policies, most parties in Europe have now developed a narrative to combat climate change. This enables voters to select different paths for the continent’s transition whether it is centred on transformative policies that seek to adapt our economic model, on innovation and private sector initiatives or on more agrarian views. The recent formulation of an environmental policy doctrine by one of the leading European far-right movements, the French Rassemblement National, is a testament to the increasing plurality of offers regarding Europe’s possible response to climate change.

How will Green losses impact Europe’s green legislation?

The so-called ‘Green Wave’, the 2015 Paris Agreement and the fact that other parties began to include climate in their campaigns gave a strong impetus for the Green Deal in 2019. Green themes spread to EU legislative initiatives in all areas during this mandate, and packages like Fit for 55 kept everyone in the Bubble busy for years.

Becoming the 4th largest group in the European Parliament came with some perks for the Greens. The allocation of speaking time and rapporteurship being proportional to the numerical strength of the group provided them with institutional strength and created space for their MEPs to introduce pro-climate arguments and narratives. Should the Greens lose this spot in the hierarchy of groups, their ability to steer reports and defend their positions would be impacted.

Still, the Greens were not part of the majority that ruled this mandate and guaranteed votes in favour of green legislation. That role fell to the informal coalition between the EPP, S&D, and Renew with the support of the Greens and often the Left. According to polls, the EPP, S&D and Renew are expected to remain the three largest political forces. At first glance, then, as long as this coalition remains in place and the S&D maintain their calls for more sustainability, the EP should retain some ambition on climate legislation in the next mandate even if there are significant losses for the Greens.

However, the EPP has recently been actively pushing back against certain pieces of green legislation and calling for some form of regulatory pause. As the largest political party, the EPP has thus far been instrumental in pushing through Green Deal legislation in Europe. However, if the fate of the EU’s climate legislation lies with the EPP, there could be reason to believe that we will see less ambition in the next mandate.

The EPP’s recent move away from the Green Deal was particularly visible in the debates surrounding the Nature Restoration Law (NRL) and subsequently the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation (SUR) - a move that sends a worrying signal to those hoping for more ambitious climate legislation.

The NRL became the first piece of Green Deal legislation to not pass the Environment Committee. Media reported that the NRL’s “rejection in the European Parliament would suggest a growing backlash against international environmental commitments.” The harsh tone of the NRL negotiations was also noted by MEPs and in the media. Some sources went so far as to accuse the EPP of eroding trust and spreading misleading claims and false information. In the end, the EPP did not succeed in killing the NRL, but it did succeed in weakening its environmental ambitions. MEP Peter Liese said, “Sure, the headline is the EPP failed, but if you look at the amendments that passed, then Timmermans and the [Socialist] lead MEP failed. There is not much left of what they wanted.”

While many expected the tone to be firmly set for the SUR to survive after EPP failed to kill the NRL altogether, they saw more success defeating the SUR during the November Plenary session. Green MEP Sarah Wiener, who led the work on the file, called the rejection a “bitter blow” for the protection of the environment and public health. Wiener blamed an “unholy alliance of the far-right, conservatives and liberals” which managed to “kill the entire position of the Parliament”. Once again, the devil was in the details. During the Plenary voting session, the amendments passed by the ‘unholy alliance’ discredited much of the Rapporteur’s ambition within the text. Ultimately it was the Greens that pushed for other groups to reject the text in the hope of referring it back to the ENVI Committee, but the final vote on the referral was crucially lost and the EP left the hemicycle without a position on the file - all but officially leaving the proposal dead in the water for this mandate.

Politically, the EPP is facing pressure of its own. While it is set to retain its position as the largest political party, polls expect the EPP to be the second biggest loser after the Greens. It is difficult to say for certain whether the shift in the EPP’s position on the Green Deal is limited to the NRL and SUR due to their perception that it could negatively impact farmers, food production and the agricultural sector, or whether it represents a more general shift. On the NRL, the EPP has insisted that it is the former, with MEP Christine Schneider saying, “we as the EPP stand by the objectives of the European Green Deal. We want the Montreal biodiversity protocol to apply across the world. But we don’t agree on the path to take”.

The EP’s composition is only one factor that can influence the ambition of the EU when it comes to climate policy. It will be important to watch the Council, which is also becoming more and more right-wing and has been pushing back against climate legislation. A group’s strength in the Parliament is also dependent on support in the Council. Having ministers that can echo or support the amendments introduced by a group in the Parliament improves the likelihood that these will reach the final text. The Greens/EFA can only claim partial support in the Council from ministers in coalitions and this is unlikely to change in the next mandate. For example, during this mandate, a coalition of 8 Member States including France, Italy and the Czech Republic pushed to weaken legislation on car emission limits, and Italy has also been very vocal in its objections to the energy efficiency of buildings legislation.

Ultimately, the outcome of the elections could see the Greens go from a situation of weak power and moderate institutional capacity to a situation of weaker power and weak institutional capacity. However, the outcomes of the NRL and SUR show that the influence of the EPP is more important for the future of green legislation, while the changing composition of the Council could also have an important impact on levels of ambition.

What are the most important things to know ahead of the elections and next mandate?

The 2024 European elections will be a key moment - not only for the Greens but for European climate legislation more generally. Climate policy in the 2024-2029 mandate will have to be ambitious if the EU is to meet its 2030 and 2050 targets. It is, therefore, important to examine the receding green wave and understand its causes. The key points to remember are:

- The Greens are doing badly in the polls, but there is still time for the situation to change.

- Nationally, Green parties have experienced ups and downs during the last mandate, but recent national elections have seen them lose a lot of support in countries where they’ve previously done well.

- Citizens still see climate change as a priority, but recent crises have put financial pressure on citizens and spotlighted the costs of the green transition and the many other issues that need to be addressed. This can also lead to the Greens being perceived as out of touch with the struggles of “average” citizens, which is a narrative that has been perpetuated by opposing parties.

- Green parties have also had to make concessions in countries in which they are in coalitions, and have increased competition from other political parties that have started to campaign on green issues.

- Green losses in the next European elections won’t necessarily mean that EU climate legislation will be less ambitious.

- The Greens were not part of the informal coalition that ruled the current mandate, and this is unlikely to change in the next mandate. The size of their group did award them important speaking times and the ability to lead on files in the EP, which could decrease if the prediction of the polls comes true.

- The political makeup of the Council and the EPP possibly reversing its support for green legislation will be other important factors to consider.